Archive for the ‘Soul City’ Category

From The Set Of The Video Shoot For Uptown Funk The Latest From Mark Ronson ft Bruno Mars

Posted in funk, hip hop, insideplaya, Music, New York, Soul, Soul City, tagged Bruno Mars, Funk, insideplaya, Mark Ronson, Soul, Soul City, Uptown Funk on EthGMT+0000| Leave a Comment »

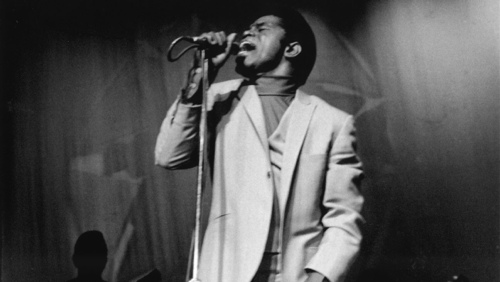

Revisited: J Period’s Breathtaking Mixtape Tribute To The Godfather of Soul

Posted in funk, hip hop, insideplaya, Music, Soul, Soul City, tagged Funk, insideplaya, J Period, James Brown, Mr. Dynamite, Mr. Please, Please, Soul, Soul City, The Hardest Working Man In Show Business on EthGMT+0000| 2 Comments »

Sent via E-Mail From My Brother @MarkRonson, ft @IAmMystikal, Feel Right

Posted in funk, insideplaya, Music, New York, Soul, Soul City, tagged Feel Right, Funk, insideplaya, Mark Ronson, Mystikal, Soul, Soul City on EthGMT+0000| Leave a Comment »

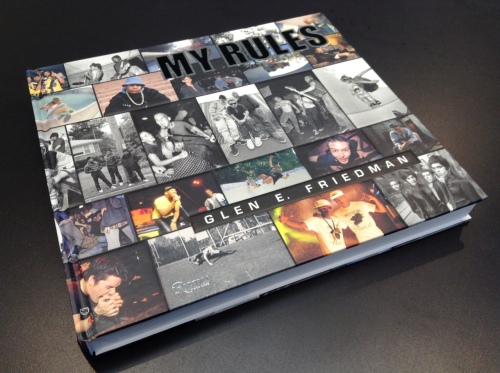

Game Recognize Game (My Contribution To My Rules, The Latest Photography Book From Glen E. Friedman)

Posted in books, Education, Glen E. Friedman, hip hop, insideplaya, Music, New York, Soul City, tagged A Tribe Called Quest, De La Soul, Def Jam, Eric B and Rakim, Gary Harris, Glen E. Friedman, Hip Hop, insideplaya, LL Cool J, North Carolina, Pinehurst, Public Enemy, Queen Latifah, Rick Rubin, Rizzoli, Run DMC, Russell Simmons, Soul City on EndGMT+0000| Leave a Comment »

Glen E. Friedman has been a friend for nearly thirty years. He is a world class photographer with a new coffee table book out on bookshelves right now. I have written the afterword for the book. Here it is…

Game Recognize Game

For many of the players found in these pages, a Glen E. portrait, magazine shoot, publicity photo, album cover, t-shirt photo, or poster coincided with the moment when the subjects were breaking through from one level of the game to the next. From a singles deal to an album, club act to arena opener, from an opener to a headliner, from gold to platinum sales status, from releasing a string of important recordings to booking their first film role, from hanging with their clique to being outta here. Whatever the next level was, Glen was there with his vision to present them as they were precisely at that moment: ascending.

Because more often than not, Glen was there when their demo was moving around the hands of the few tastemakers who were empowered to sign them or when their first 12-inch single dropped and he heard it. He was there early because he was not merely an outside observer or on an anthropological expedition—he was a member of the movement and the community that he captured so dynamically and promoted relentlessly.

That’s how we met. I was there too, and, like him and many others, I was engaged in the day-to-day struggle of building the small but tight hip-hop nation into the international hip-hop culture and global business force that it has become. We were both living in New York and we’d see each other around campus. I had been the head of promotion for Def Jam, moved on to work at several other companies but kept close ties with my man Russell “Rush” Simmons. Because you could generally find Glen where the action was, he rolled with Rush too, and we were all friends and members of each other’s extended families.

In fact, “Rush” had a four-hundred-square-foot “mini” duplex, a walkup apartment in the dead center of Greenwich Village that Glen and I had keys to, crashed in, and where we all operated as unofficial roommates for a time. The place had a sky-blue facade with illustrations of pigs and elephants descending to the ground via parachute. Man, if those pigs could talk.

I made a living by putting records on the radio for labels that were cool enough to sign dope joints, but had no clue about how to get them any exposure. These small indie, mom-and-pop labels that were the first to develop hip hop and turn it into a cultural force, before multi-national corporations turned it into an economic one, were also the ones that consistently hired me and Glen. I got their records played, and he directed and shot their artwork.

So we weren’t only members of a community that was still getting most of its juice from the underground—a movement that had yet to be fully recognized by mainstream media, and a culture that at the time, very few referred to as such. We were also part of a loose network of young folk mixing shit up every which way we could, hustlers who made their way in Ronald Reagan’s America and Ed Koch’s New York, who attempted to instigate change in the status quo and use art to improve our lot in life.

Hustling times call for moves to be made, so while I was on a mid-’80s business trip to LA for a Black Radio convention. I ran into Glen, who was still based in Cali, and looking out for Def Jam and Russell Simmons’s acts when they were in town. I was there networking, raising my profile and looking for checks. Glen was passing through with Lyor Cohen. Glen and I didn’t know each other well then, so I hit him with it, “Where you from?”

Homie told me he grew up in LA, but started school in Englewood, NJ, and was born in Pinehurst, North Carolina. Later, he told me he really was a bicoastal kid who shuttled back and forth to see his dad on the east coast. He said living in Englewood at a young age really opened his eyes to racism and discrimination. He relayed a story about his best friend, who was two years older than Glen and Native American, and who was assaulted in a barber’s chair when his mom took him to get a haircut from white barbers! They fucked his hair up, and when they cut it all off, it left a mark on Glen that he never forgot. He also was living in Englewood when Martin Luther King, Jr., was assassinated, which also left a huge impression on him.

Pinehurst was my own mother’s birthplace, and Englewood—less than a mile outside of Manhattan—was home to the first fully integrated school system in America. The city has produced artists like John Travolta, Brooke Shields, Richard Lewis and Karen O. It is the place where Sugar Hill Records was based when they signed Grand Master Flash, and got the hip-hop ball rolling when they dropped “The Rappers Delight” by the Sugar Hill Gang. It is a place where creative freedom flourished, and many artists who benefited from it called it home. It is the place where jazz greats Dizzy Gillespie and Sarah Vaughan once lived and Thelonious Monk died. Soul Man, Wilson Pickett lived there along with Rock & Roll Hall of Famers, the Isley Brothers. I know the town well; I was born there, grew up there, and broke into the record business by working at Sugar Hill. I was actually a classmate of Glen’s Native American friend from grade school. But Glen and I would not discover how closely we were tied together through our shared background until much later.

It is in that background where you may find clues as to why Glen, a kid of Jewish descent with a vegan diet, and far-left-leaning political tendencies; a kid who was already a graduate of the nascent skateboard and American punk scenes, rolled so easily with black folks on the come-up. It may explain why he relentlessly promoted the demos of eventual Rock & Roll Hall of Famer Chuck D and Public Enemy to countless tastemakers with the following prediction: “These guys are going to do for hip-hop what The Clash did for rock & roll.” Why he was the one to put me up on the first double sided De La Soul 12-inch, “PlugTunin’”/”Freedom Of Speak.” And why on the night after he first played the record for me, we went to see Queen Latifah’s first show ever, in an abandoned junior high school gym that on weekends doubled as a space for an underground party called “Amazon”; and why he walked around in the dead of winter with a self-recorded cassette of the De La joint with the hopes that he’d run into someone with a tape recorder and he could put them up on it too.

Glen was also the guy who shopped the first A Tribe Called Quest demo to that small group of cutting-edge labels that comprised the early rap business. And the one who first played Ice Cube’s Amerikka’s Most Wanted for me, with its early example of east-meets-west collaboration between Cube and the production team that laced the Public Enemy records with all that heat, the Bomb Squad. He dated beautiful black girls who wound up as doctors who graduated from Ivy League schools, and this may have been where he first learned that talent has no color and can never be held back by arbitrary boundaries.

With the exception of his confusing and misplaced love of the Pittsburgh Pirates, Glen has always been on point, but if you dig a little deeper, more facts can be unearthed. Pittsburgh was the team where MLB executive Branch Rickey landed, after he brought Jackie Robinson to the Dodgers, thereby breaking the color line. Rickey continued his progressive and contrarian ways when he built an organization that not only signed the Hispanic legend, Roberto Clemente, but would eventually be the first Major League team to start an all black lineup. Of course, to Glen, this was baseball like it oughtta be.

The late Dock Ellis was the pitcher who took the mound on the day the team sent that first all black lineup on the field. The legendary right-handed pitching rebel and malcontent threw smoke. Ellis would evolve into a symbol of black rebellion and a counter-culture hero who confounded the front office and baseball’s image-makers with his unwillingness to adhere to the status quo. By chance, Ellis met a loud mouthed, eleven-year-old Pirates fan yelling for an autograph from the stands at a game in Shea stadium. This resulted in Dock developing a friendship with young Glen Ellis Friedman. He was probably the first of many fuck-you heroes to cross paths with my man.

Like the artists that he photographed, Glen E. Friedman was a product of the underground and his commitment to youth culture, progressive politics, art, artists, and artistry is unparalleled among my collaborators, peers, associates, and friends. He is my Senior Vice President of Artistic Integrity, my comrade in arms, my man a-hundred-fifty grand, my Nigga. He made a home among talented outsiders, and by using his talent, his gifts, his contacts, and his power without discriminating, he lent credibility to the efforts of others, and thus greater access to the larger world. He became an advocate for hip-hop at the time when it was most in need of advocacy. He trafficked in authenticity, as well as conceptualized and documented images of rebels at work. He served it fresh daily.

And now you’ve made a move, you picked this book up, and you’re reading an essay in a publication filled with portraits that depict pioneers, legends and stars at important times in their lives and in their careers. You’re one of the smart ones, huh? You know what’s up? You’re probably a leader in your field and a top shelf player in your chosen area of expertise.

A top dog, a don. If not, then you have a book filled with images of people who are and were. And if you’ve got a combination of the right hustle, gifts, and skills, and the time is right, then maybe this book will help close the gap between where you are now and a spot at the top of the heap. Or maybe it will serve to remind you of what it was like when you were last there, and help you to recall the required swagger to get you back.

But remember this: the players in these pages, were not in it for the shine. They did it because they could. Their ethos was art for art’s sake, because it was not apparent that you’d get rich when you put your thing down back then. It was more likely that you’d put out a record that no one but your friends and family would ever hear. These players did it for love. If you got rich or famous, that was a result of a lot of sweat, more than a few tears, and the stars properly aligning in your favor; it was not the objective. They grabbed a mic, spit a rhyme, rocked the party, or dropped a joint because they needed to, wanted to, had to. They got on a roll, and used all of their heart, all of their training, and all of their skills to blaze that moment, and the next one, and the next, until they caught fire. And when they got just hot enough, Glen E. Friedman took their picture.

insideplaya

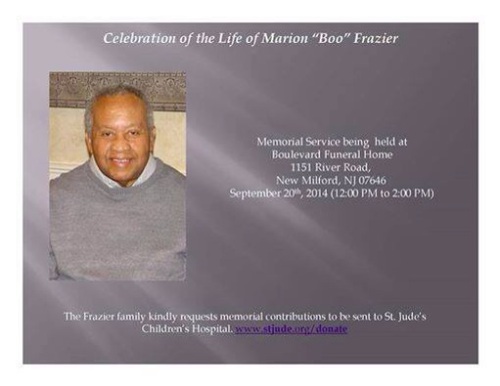

Service & Donations In Memory Of Boo Frazier

Posted in Charity, funk, insideplaya, Jazz, Music, New York, Soul, Soul City, Uncategorized, tagged A&M Records, Boo Frazier, Dizzy Gillespie, Herb Alpert, insideplaya, Jazz, Jerry Moss, Soul, Soul City on EthGMT+0000| Leave a Comment »

Soul City

Posted in funk, hip hop, insideplaya, Music, Soul City on EstGMT+0000| 2 Comments »

Coming this Saturday August, 2, the playa will begin a new phase. Live over IMG Radio, on a weekly basis, I will be spinning Soul, Funk and Hip Hop classics, with the occasional new, rare and unsigned release from 7-11 PM EDT. See ya there.

The Playa’s Rules

Posted in books, Glen E. Friedman, hip hop, insideplaya, Music, New York, Soul City on EstGMT+0000| 4 Comments »

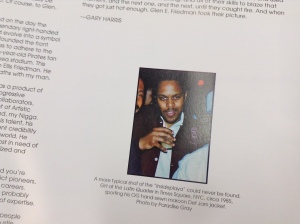

My brother Glen E. Friedman is a world class photographer whose iconic images have been the cover art for recordings by Public Enemy, Ice-T and Run/DMC. He is one of the most important photographers to have participated in Hip Hop’s golden age. In addition to his groundbreaking work in Hip Hop, he was one of the earliest to document the American Punk scene, and the nascent skateboarding phenomenon with his incredible eye. He is one of the most gifted people that I know. This fall, he will be releasing a massive retrospective in a coffee table edition through Rizolli Publishing. The 7lbs plus book will be comprised of hundreds of images, of which 80% have been previously available in Glen’s self published, and now out of print, Fuck You Heroes book, and its sequel, Fuck You II. Along with the previously unseen 20% of the photos, will be essays by Rakim, Ice-T, LL Cool J, Henry Rollins and Rick Rubin among others. The book includes a forward from Shepard Fairey and a 2,000 word afterword from the playa. Here are a couple of shots of my two pages in the book. S/0 to Jessica Fuller our editor at Rizzoli.

The Preacher

Posted in funk, insideplaya, Music, New York, Soul, Soul City, tagged Bobby Womack, insideplaya, James Brown, Soul, Stevie Wonder on EthGMT+0000| Leave a Comment »

BOBBY WOMACK

Now that the tears have finally stopped, the disbelief has subsided and the skepticism has been addressed; the attempt, to organize my thoughts in a fitting tribute to one of the greatest recording artists that America has produced, seems a little more possible. Bobby Womack the Soul singer who gave us “A Woman’s Gotta Have It”, “I Can Understand It”, “If You Think You’re Lonely Now” and “Across 110th Street” has died at the age of 70. At this time, no cause of death has been confirmed.

In my formative years – like most Black folks my age – I went to church often. Because the Civil Rights movement was organized and led, mostly, by preachers, the feeling of secularized Gospel singing had greater resonance. The church was the center of Black life, and it informed the politics and culture of the day. If you’re too young to remember, or you were old enough but unaware of the social and political fabric of the Black American community at the time, imagine this: A people engaged in a daily struggle for freedom to be educated in any fashion they chose, to live where they wanted, to vote for whomever they wanted to without fear, to earn a fair day’s pay in return for a full day’s work and equal protection by and under the law. And while all of this is going on, people trained in the church are singing of your hopes, joys, pain and triumphs in the deepest, purest and most emotional and inventive ways imaginable – that’s why the call it Soul Music. Bobby Womack, in that time, in that way and in that genre, was a master.

In the New York of the early seventies, WWRL, “Super 1600 on your AM dial,” was the hub for Southern based, church influenced singing. It was on their air that I first discovered the mournful, bluesy, gritty and funky voice of Bobby Womack – sounded like sandpaper with honey poured over it.

I was in the third or fourth grade, and “Harry Hippy” his tale of a vagrant who lived the free life, on Sunset Boulevard in Hollywood, struck a very deep chord in me. The frustration that Womack expressed because he couldn’t inspire Harry to – as my late mother used to say – “do better,” was haunting. You could hear the ache pouring out of the radio. At that time, James Brown, Sly Stone, Aretha Franklin and Funk were the flavor, but Bobby Womack’s vocals and lyrics managed to cut through it all on the strength of pure emotion. He had a grown man’s depth, and you could hear it in his voice.

Earlier this week, an Internet based hoax had killed him off before his time. My Facebook newsfeed had several posts in tribute to the Rock Roll Hall of Fame caliber “midnight shouter”. Tonight, in disbelief, I contacted Chris Rizik of soultrax.com, and the legendary Sparkie Martin, a former manager who had introduced me to Womack years ago. They both confirmed that he was gone. My heart broke.

Bobby Womack began his career as a member of a Gospel group that he and his brothers formed. They were signed to a label operated by the great Sam Cooke. In the mid-sixties, Womack broke away to pursue a solo career that resulted in a string of hit albums and singles. Struggles with addiction and poor health marked his later years until Richard Russell of London’s XL Records returned Womack to the studio in 2012.

These tributes are becoming more and more frequent, and unfortunately, more and more necessary. It seems that the truly great contributors to Soul Music are passing on daily, and with each one’s death, the living witnesses to one of the great eras in American culture passes on.

Even as I write this, I can recall the opening lyric to Womack’s heartfelt ballad “That’s The Way I Feel About ‘cha,” If you get anything out of life/you got to put up with the toils and strife – a simple and brilliant assertion that is no less true than when I first heard it over forty years ago. Bobby Womack, a man they called “The Preacher”, was a man of his time who knew what he was talking about.

insideplaya

An Open Letter To D’Angelo

Posted in insideplaya, New York, Soul, Soul City, tagged ?uestlove, Brian Koppelman, Brown Sugar, D'Angelo, EMI, Gary Harris, insideplaya, Nelson George, Neo-Soul, NPR, Voodoo on EthGMT+0000| 5 Comments »

Nelson George and D’Angelo

Thank you for showing the good taste that you have in coming to this blog. I truly appreciate your interest in my writing. Sorry if you have come to see something that is no longer here, but indeed it had already served its purpose and then some. Please feel free to peruse and enjoy other writings and posts.

thank you,

insideplaya